Abstract:: In this work, we investigate leveraging multiple modalities to reduce the false negative rate in breast cancer screening with artificial intelligence (AI). Recent work has shown that neural networks can be trained effectively for single modality breast cancer detection. Due to occlusions, some lesions are not visible in certain modalities. Our goal is to improve system performance by leveraging multiple modalities. Single modality networks trained independently with a simple averaging late fusion strategy is used as a baseline. With a transformer-based late fusion strategy, we beat the baseline by 0.019 AUROC.

Introduction

Breast cancer is amongst the top ten largest contributor to global deaths for women. From an AI perspective, making advancements towards tackling breast cancer is possible due to the volume of data made available by well established screening programs. Annual screening mammography exams in the US, for example, is common practice for women above 40. Such screening exams consists of low dose X-ray from two views for each breasts; bilateral craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO). Women with dense breast typically undergo further screen via ultrasound as lesion in dense breast may be occult in mammography images. Upon examining the medical images, radiologist determine if further diagnostic exams are required. When a lesion is seen, radiologist assess the probability of malignancy for the lesion reported as a BI-RADS score between 1 and 6. A BI-RADS 1 and 2 suggest low probability of malignancy. A BI-RADS 3 requires a short-interval follow-up, while BI-RADS 4 and above requires an immediate biopsy due to high probability of malignancy. Only once a biopsy is done, can a lesion be confirmed as malignant or benign.

To help radiologist make more accurate diagnoses, neural networks have been implemented to analyze medical images. Most of the recent work done for breast cancer is focused on training networks with a single modality. We would like to leverage multiple modality to both take advantage of as much patient history as possible and combat presence of occluded lesions in some modalities or views.

The problem is formulated as a multi-instance and multi-modal classification task. Given ultrasound and mammography images from a patient, the goal is to predict whether or not a malignant lesion is present.

Related Work

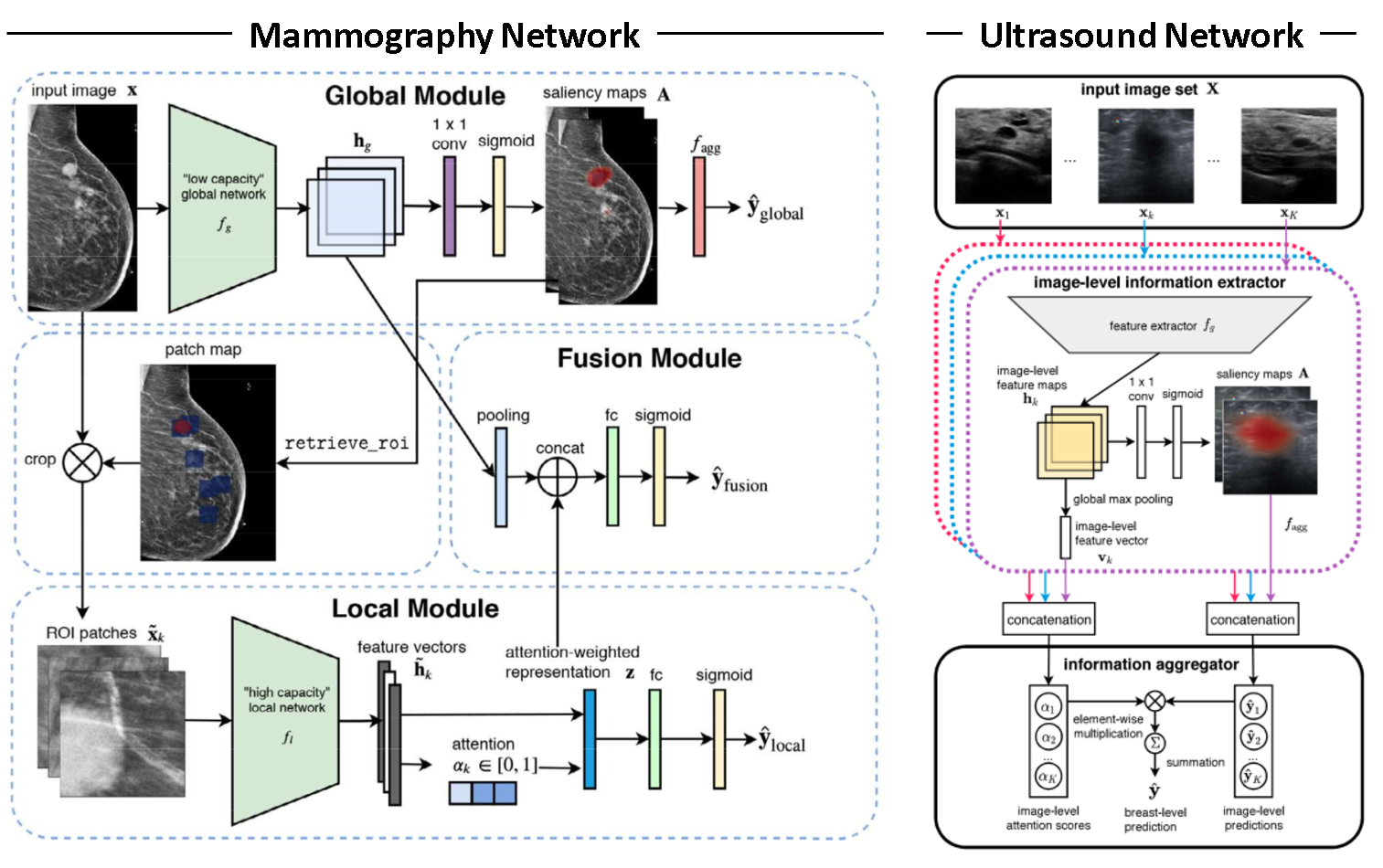

This work builds extensively on Shen et al. 2021 and Shen et al. 2021b. Both papers are focused on the development of highly specialized single modality networks for ultrasound and mamography shown in Figure 1. We intend to build on those networks by adding a fusion module to yield a fused class prediction.

Due to the large resolution of mammography images (2944 by 1920 pixels) and the relatively small size of a potential lesion, authors of Shen et al. 2021 focus on developing a model that has the ability to focus on both local features and global ones. The difficulty with with diagnosing breast cancer from mammography images is that both local features, such as lesion shape, and the global features, such as tissue density distribution and breast structure, are critical factors to consider for the diagnosis. To account for this, the authors developed a novel network called globally-aware multiple instance classifier (GMIC), which consists of a global and a local module. The global module identifies smaller regions of interest and learns the global structure of the breast, while the local module inspects smaller relevant features in the identified regions of interest. Features from the two module are then combined to yield a final prediction.

In Shen at al. 2021b, a neural network is developed with the objective of reducing the false-positive rates as radiologist breast cancer diagnosis with ultrasound images are typically associated with higher false-positive rates. The network consists of a resnet feature extractor followed by a one-by-one convolution with a sigmoid activation to yield saliency maps. The saliency maps are aggregated to a prediction via top-k pooling. The resulting image level prediction are aggregated to breast level predictions via an attention mechanism.

Experimental Evaluation

Data

Our dataset consists of medical images and biopsy reports of approximately 300,000 patients. The dataset is a product of Nan et al. 2019 and Shamout et al. 2021. Imaging modalities in the dataset include mammography, ultrasound, and MRI, but we will only be using ultrasound and mammography modalities in this work. Patient records have been grouped into episodes and each episode has been associated with one of two class labels extracted from the biopsy report via an NLP pipeline; contains or does not contain a malignant lesion.

Methodology

We approach multi-modal learning through a late fusion strategy. Single modality networks, shown in Figure 1, trained independently with a simple averaging late fusion strategy is used as a baseline and yields 0.867 test set AUROC. We will be comparing other late fusion strategies to this baseline.

Two categories exist in our late fusion setting; prediction fusion and late representation fusion. Prediction fusion entails the fusion of predictions outputted by each single modality network, depicted in Figure 1, via an aggregation function such as simple averaging or an attention-based function. Late representation fusion entails the fusion of late representations from each single modality network to yield a single prediction via a neural network.

The loss function associated with training prediction fusion models is

\[L(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{\hat{y}},\mathbf{A}) = \textrm{BCE}(\mathrm{y}, \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{fusion}) + \textrm{BCE}(\mathrm{y}, \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{US}) + \textrm{BCE}(\mathrm{y}, \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{M}) + \beta \sum_{(i, j)}|\mathbf{A}[i, j]_M| + \gamma \sum_{(i, j)}|\mathbf{A}[i, j]_{US}| \tag{1}\]where \(\textrm{BCE}\) is the binary cross-entropy loss function, \(\mathbf{y}\) is the label, \( \mathrm{\hat{y}_{fusion}} \) is the fused class prediction, \( \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{US} \) is the class prediction from the ultrasound network, and \( \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{M} \) is the class prediction for the mammography network. As shown in Figure 1, both the ultrasound and mammography networks have been designed to output saliency maps, given as \( \mathbf{A}[i, j]_{US} \) and \( \mathbf{A}[i, j]_{M} \) in Equation 1. Throughout this paper we will refer to the first three terms from Equation 1 as modality-specific BCE loss and the last two terms as Class Activation Map (CAM) loss. Note that the CAM loss acts as a regularizer to limit high activation regions in the saliency maps. \( \beta \) and \( \gamma \) in Equation 1 are weighting factors to control the scale of CAM loss relative to the modality-specific BCE loss.

For late representation fusion, the loss function is given by

\[L(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{\hat{y}},\mathbf{A}) = \textrm{BCE}(\mathrm{y}, \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{fusion}) + \beta \sum_{(i, j)}|\mathbf{A}[i, j]_M| + \gamma \sum_{(i, j)}|\mathbf{A}[i, j]_{US}|. \tag{2}\]Late representation fusion experiments suggest that modality-specific BCE loss results in performance degradation hence the \( \textrm{BCE}(\mathrm{y}, \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{US}) \) and \( \textrm{BCE}(\mathrm{y}, \mathrm{\hat{y}}_{M}) \) terms were dropped from the loss function resulting in Equation 2.

Results

We experimented with three different variants for prediction fusion. The first involves training the single modality networks simultaneously with a simple averaging fusion strategy. The second uses a gated attention mechanism (GAM) to perform a weighted average of the single modality predictions (Ilse et al., 2018). GAM module is given by

\[\boldsymbol{\alpha}_k = \frac{\mathbf{W}^{\intercal}\tanh(\mathbf{V}\mathbf{v}_k^{\intercal})\odot\textrm{sigm}(\mathbf{U}\mathbf{v}_k^{\intercal})}{\sum_{j=1}^K \exp\{\mathbf{W}^\intercal(\tanh(\mathbf{V}\mathbf{v}_j^\intercal)\odot\textrm{sigm}(\mathbf{U}\mathbf{v}_j^{\intercal})\}} \tag{3}\]where \( \mathbf{v}_k \) is the concatenated late representation feature vectors from ultrasound and mammography networks and \( K \) is the total number of images per episode. \( \mathbf{U} \), \( \mathbf{V} \), and \( \mathbf{W} \) are learnable parameters of the GAM module. The output of GAM, given by \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_k \), are attention weights associated with each late representation feature vector. Note that attention weights associated with one episode are parameterized such that they sum to one. Aggregating the resulting attention weights to the breast level is done by summing \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_k \) associate with each modality. This aggregation procedure produces \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{US} \) and \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_M \) given by

\[\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{US} = \sum_{k \in US} \boldsymbol{\alpha}_k, \quad \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{M} = \sum_{k \in M} \boldsymbol{\alpha}_k. \tag{4}\]A fused prediction is produced by

\[\mathbf{\hat{y}} = \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{US} \mathbf{\hat{y}}_{US} + \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{M} \mathbf{\hat{y}}_M \tag{5}\]where \( \mathbf{\hat{y}}_{US} \), \( \mathbf{\hat{y}}_M \), and \( \mathbf{\hat{y}} \) are the ultrasound, mammography, and fusion class predictions respectively.

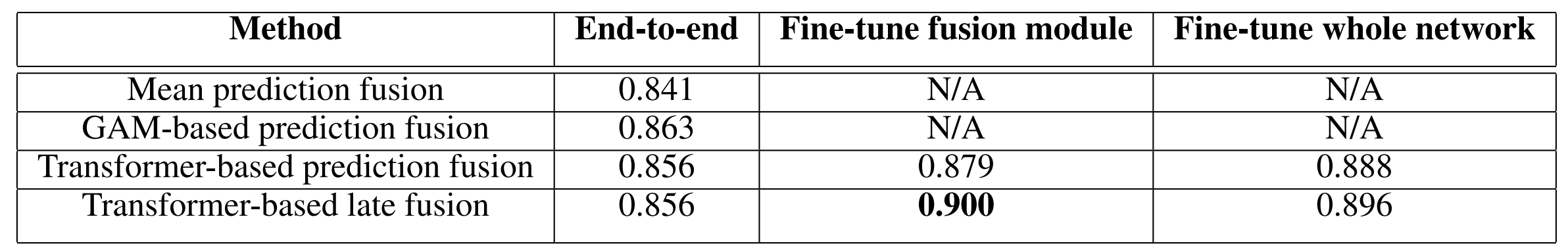

The third prediction fusion method uses a transformer encoder architecture as an attention mechanism to perform the weighted average operation given by Equation 3. As depicted in Figure 2, late representations from the single modality networks are used as inputs to the transformer encoder. A learned cls token is added to the feature vector input and a learned modality embedding is added to the feature vector prior to being fed through the transformer. Lastly, the cls token encoded representation is fed through a linear layer followed by a softmax activation function to yield \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{US} \) and \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{M} \). For all prediction fusion experiments, we use a transformer encoder architecture with 3 layers and 4 heads.

Our late fusion approach follows a similar form to the transformer based prediction fusion approach discussed previously. However, rather than using a transformer encoder architecture to output \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{US} \) and \( \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{M} \), we output the fused class prediction, \( \mathbf{\hat{y}} \), directly. For all late fusion experiments, we use a transformer encoder architecture with 6 layers and 8 heads.

For all late fusion methods, we ran three sets of experiments; (1) network is trained end-to-end, (2) pre-trained weights are loaded for single modality networks and only the fusion module is trained, and (3) pre-trained weights are loaded and frozen, fusion module is trained until convergence, followed by unfreezing all weights and fine-tuning the whole multi-modal network until convergence. Note that the pre-trained weights for the single modality networks are obtained from the baseline. Adam optimizer is used for all experiments with weight decay value of \( 10^{-5} \), \( \beta_1=0.9 \), and \( \beta_2=0.999 \). Grid-based hyperparameter search was conducted for the learning rate and the single modality network configuration. \( \beta \) and \( \gamma \) from Equation 1 and Equation 2 were set to 0.1 and 0.01 respectively.

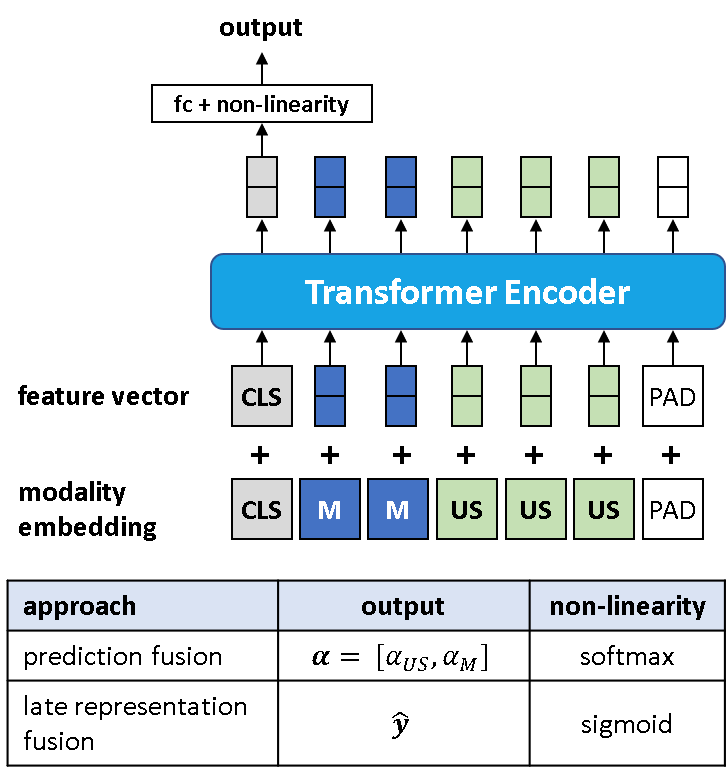

Late fusion experiment results are shown in Table 1. Column headers “End-to-end”, “Fine-tune fusion module”, and “Fine-tune whole network” in Table 1 correspond to experiments (1), (2), and (3) discussed in the prior paragraph respectively. Loading pre-trained weights for the single modality networks before training yields a significant improvement in performance. Fine-tuning the whole network yields inconclusive results as performance does not necessarily increase in comparison to using a pre-trained single modality network and fine-tuning just the fusion module. The best performing model is the pre-trained transformer-based late fusion model in which only the fusion module is fine-tuned, resulting in 0.900 validation AUROC.

Discussion

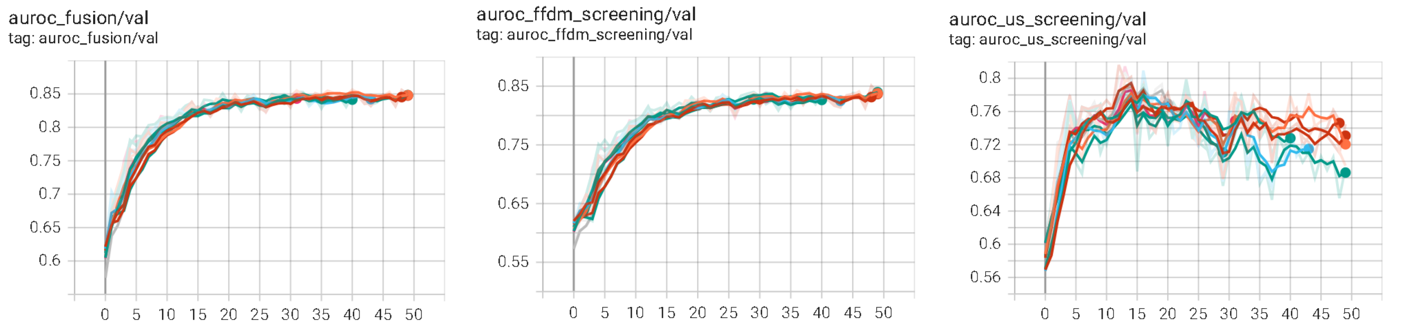

An ubiquitous factor that hinders performance across all our experiments is the imbalance between learning from the two modalities (Wu et al., 2020). Figure 3 shows sample learning curves for a prediction fusion model that demonstrates the imbalanced learning process. The three charts depicted in the figure are associated with validation AUROC for the fused class prediction, the mammography network class prediction, and the ultrasound network class prediction. All the networks are trained simultaneously in this scenario with one learning rate. It appears that the performance of the fused prediction plateaus. Note that there are two opposing factors that lead to this plateau behavior; past 15 epochs (1) the mammography network performance increases, while (2) the ultrasound network performance decreases. It appears that the point of overfitting occurs much earlier in the ultrasound network in comparison to the mammography network. We suspect that one of the culprits of the imbalanced training is the training data distribution. The training data has many more mammography exams than ultrasound exams which likely contributes to imbalanced training between the two modalities (329,709 mammography exams vs. 96,358 ultrasound exams). This may be remedied by using different learning rates for different parts of the multi-modal network such that the point of overfitting for each part of the network coincide.

Conclusion

We have implemented and trained multi-modal networks for breast cancer detection using a late fusion strategy. From the methods we experimented with, the best performing approach is a late representation fusion strategy with a transformer encoder architecture which has been trained by first loading pre-trained weights and fine-tuning only the fusion module. The resulting test set AUROC of this approach is 0.886 and beats the baseline by 0.019. For future work, we suggest leveraging the cross-attention operation in a transformer for late fusion as done in Lu et al. 2019. To better align representations extracted from each modality, we suggest adding a cross-modality matching objective as done in Tan et al. 2019. One can also explore intermediate fusion strategies through the use of Multi-modal Transfer Module as the intermediate fusion network (Vaezi et al. 2019).

References

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey, et al. “An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

- Ilse, Maximilian, Jakub Tomczak, and Max Welling. “Attention-based deep multiple instance learning.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018.

- Lu, Jiasen, et al. “Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.02265 (2019).

- Shamout, F. et al. The NYU breast ultrasound dataset v1.0. Tech. Rep. (2021).

- Shen, Yiqiu, et al. “An interpretable classifier for high-resolution breast cancer screening images utilizing weakly supervised localization.” Medical image analysis 68 (2021): 101908.

- Shen, Yiqiu, et al. “Artificial Intelligence System Reduces False-Positive Findings in the Interpretation of Breast Ultrasound Exams.” medRxiv (2021b).

- Tan, Hao, and Mohit Bansal. “Lxmert: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.07490 (2019).

- Vaezi Joze, Hamid Reza, et al. “MMTM: multimodal transfer module for CNN fusion.” arXiv e-prints (2019): arXiv-1911.

- Wu, Nan, et al. “The NYU breast cancer screening dataset V1. 0.” New York Univ., New York, NY, USA, Tech. Rep (2019).

- Wu, Nan, et al. “Improving the Ability of Deep Neural Networks to Use Information from Multiple Views in Breast Cancer Screening.” Medical Imaging with Deep Learning. PMLR, 2020.